Launch of farmer-led TB governance in New Zealand

Summary

In 1995 New Zealand submitted their bovine TB control strategy to the Minister of Biosecurity. Progress to-date has been outstandingly successful. Dr Paul Livingstone was the TB Eradication and Research Manager for the TBfree New Zealand programme. In 2011, Dr Livingstone was awarded the Queen's Service Order for services to veterinary science, particularly for work on bovine TB. Although Dr Livingstone retired in the summer of 2016, he still works as a consultant and this article presents events which took place in New Zealand as recalled by Dr Livingstone. In doing so this article looks at what happened in New Zealand in the formative years. This includes years leading up to 1995 when the strategy was submitted to the Minister of Biosecurity and TB levels started to tumble.TB histories in New Zealand and England

Questions and answers

On 28th June 2014 the following questions were submitted to Dr Livingstone in order to gain a better understanding of how New Zealand set up their TB control framework. In the cover note which Dr Livingstone sent with his answers, Dr Livingstone stated the following.

I am firmly of the opinion that farmers need to be involved in the programme as they are the true beneficiary of

it. Our experience would suggest that the best way to make farmers want to take accountability and responsibility

is to make them contribute towards the programme which then gives them the right to become involved in managing

the disease at a national and regional level.

Question 1

I have been trying to assess farmer opinion in England and Wales for working more collectively to control TB. However the feedback which I have been getting is deep mistrust amongst farmers. I think in view of past experiences with farming levy organisations there is concern that funds provided by farmers such as through a levy to control TB would be squandered.

I appreciate that you have already kindly provided me with useful and detailed information, but would you by any chance be able to give me a little bit more information on initial steps which were taken by New Zealand to set up a framework and some insight into how New Zealand selected personnel both on the board and regional teams. If you can give some guidance on criteria for deciding how remuneration packages were assigned to staff, how paid and volunteer staff were enrolled, and some insight into terms of engagement both at board and regional level, this would be very helpful. Essentially what I would like is a little bit more information which expands on the following extract taken from Reference 1.

The situation began to change with the development of the national TB control strategy and the AHB's network of

15 regional TBfree committees. The committees are made up primarily of farmer volunteers and local stakeholders,

who communicate, advocate and support the delivery of the strategy in each region.

Historically, the strategy aimed to curb and slightly reduce the number of infected herds, but a lack of resources for controlling TB in wildlife meant the disease continued to spread in the possum population.

Historically, the strategy aimed to curb and slightly reduce the number of infected herds, but a lack of resources for controlling TB in wildlife meant the disease continued to spread in the possum population.

Dr Livingstone's answer to Question 1

The major initiating factor in getting farmers to fund the TB control programme was the government of the day requiring farmers to fund 48% of the control programme in 1987 increasing to 66% by 1989. It was as a result of this action that farmers strongly advocated for "user pays - user says" - and hence the Animal Health Board (AHB) came into being (under the legal framework of the Ministry of Agriculture [MAF] from 1989 to 1998. After 1989 the AHB became an independent legal body for controlling bovine TB. In parallel with the establishment of the AHB in 1989, MAF was also developing new legislature which became the Biosecurity Act 1993. This Act included a section on National and Regional Pest Management Strategies and set out the requirements that an organisation would need to meet to be considered a Pest Management Agency under this Act.

These included:

- Setting objectives (time-bound, specific and measurable - with annual milestones)

- A costed plan that describes how the objectives would be delivered and by when

- A cost-benefit analysis

- Funding stakeholders agreeing to the objectives and strategy plans and to the funding of it, with a requirement for a funding review every five years.

So the critical components in our TB control programme were:

- Early recognition that TB possums were the main source of infection for cattle in defined areas of New Zealand

- The ability to kill possums as they were not a native animal

- The lack of progress in controlling TB under Government Agencies (MAF) due to lack of funding and lack of knowledge

- The requirement by government that from 1987 farmers would be funding 48% if the programme increasing to 66% by 1989

- Farmers accepting that ruling, but then demanding that they as the main payers should be the main sayers in the programme and thus as the AHB, took over the TB control programme policy, allocation of resources and the programme direction

- The Biosecurity Act 1993, with a section enabling organisations such as the AHB to become an independent Pest (M. bovis) Management Agency with the legal power to administer the TB control programme

- The requirement to have strategy objectives, a costed plan and gain agreement from all funders to fund the strategy

AHB Board Directors were appointed by a committee made up of representatives of the funding organisations, namely Dairy NZ, Beef and Lamb, Deer NZ, central and regional Government. Board Directors are paid based on a recommendation from the representatives committee – who would seek legal assistance in determining the level the Board should be paid. Members elected onto our Regional TBfree committees are managed at a local level and normally are determined by the local dairy, beef and deer farmers in their area. Members on regional TBfree committees initially gave their time freely, and received a “mileage allowance”. In recent years they have also received a small daily fee of about $150 per day.

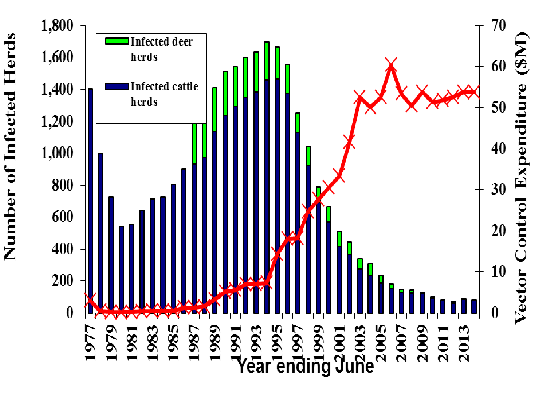

The progress of the New Zealand TB control programme was limited by the amount of money allocated to possum control. As you see from the following figure, funding for possum control didn't start increasing until the first strategy came into being in 1995/96, followed by a large increase for the second strategy which started in 2002/03. The amount spent on TB testing due to contracting out TB testing and a reduction in compensation for TB reactors due to our success has meant that this figure has remained pretty static over time. Costs of administration have increased though as we have developed software, GIS capability and taken over direct management of the disease and vector control programmes.

Question 2

Question 2In the UK, farming trade unions are often referred to in online debates regarding TB policy and understandably have been quite vocal in resisting suggestions that farmers pay a greater contribution towards TB control and compensation. I understand that members of the National Farmers Union in England have been involved in setting up the pilot culls for which the first year was completed last year. Unfortunately no reliable data was gathered which could be used to assess how thoroughly ground was covered by the contractors assigned to shoot badgers in the pilot zones. This suggests to me that certain areas to which access was given were not treated properly. (Editor note: On 8th November 2017 Natural England released data illustrated in Reference 4. This data covers 4 years of culling and gives some insight into badger cull thoroughness.)

Dr Livingstone's answer to Question 2

We had instances in New Zealand during the early aspects of our programme where farmers in some regions elected to fund possum control themselves. However, under such a regime, the programme actually went backwards. It wasn't until AHB took over the payment and contracting of the vector control programme for the whole of these regions that progress began. Thus we found that allowing farmers to independently decide what they would pay or whether they would contribute was not a logical solution when dealing with a TB vector that has no respect for farm boundaries. In our case, it require possums on all farms and forests in an area to receive possum control – this can only be managed either centrally or regionally, but not locally.

Question 3

Have farming trade unions played a significant part in shaping and carrying out TB control policy in New Zealand?

Dr Livingstone's answer to Question 3

We don't have farmer trade unions – we have a central and regional Federated farmer organisation, which farmers can elect to belong to. Our industries Dairy New Zealand, Fonterra, Beef and Lamb and Deer New Zealand are important with respect to funding the strategy. Federated farmers, whilst representing all farmers, don't actually contribute any funds to the strategy. Nevertheless, they are always very supportive of our programme.

Question 4

What I would ultimately like to do is to identify a distinguishing feature between the systems in NZ and the UK apart from the obvious one of the principal wildlife vector being introduced in NZ and native in the UK. Perhaps I need to know a little bit more about how New Zealand formed teams at regional level to ensure strong and sustainable commitment from these teams. I have been studying the valuable information which you have already provided in the references listed below.

Dr Livingstone's answer to Question 4

The following is an excerpt from a paper that I am co-authoring which lists the factors that we consider have been important in the success of New Zealand's TB control programme, which may be of benefit:

We consider the major drivers underpinning the sustained success of the NPMS (National Pest Management Strategy) include:

- agreement between stakeholders on strategic objectives, TB control methods and policies, based on robust processes of consultation and a resulting sense of partnership and ownership of the strategy. Surveys have regularly showed very strong (85%) farmer support for the NPMS (Anonymous 2011b)

- the establishment of a dedicated management agency solely responsible and accountable to its funders for developing and implementing an agreed strategy for controlling bovine TB

- durable strategy funding agreements between the beef, dairy and deer farming sectors as well as central and local government resulting in a stable and sustained level of funding, averaging $NZ $81.2 million per annum from 2002 to 2013. This stability has enabled the development and implementation of long term plans to meet the strategy objectives

- the initial policy of out-sourcing service delivery to organisations with established capacity and expertise, followed by progressively and selectively developing in-house managerial and technical capacity and capability in key areas

- effective communications with farmers to support programme delivery, notably through a dedicated in-house contact centre

- designing and building information systems and databases to manage and record disease and vector control activities. These also provided the basis for the development of a business model which facilitated the contracting of field services such as cattle TB testing and vector control in a competitive environment. Implementing these changes provided greater control over contracted services and long term cost savings

- improvements in livestock TB management including more accurate diagnostic testing, tighter controls on movement of stock from infected herds, compulsory ear-tagging of cattle and deer to identify their herd of origin for more reliable tracing of infection sources, and DNA typing of M. bovis isolates to assist in epidemiological investigation of herd infection cases (Buddle et al. This issue)

- specific industry funding agreements to help maintain farmer 'buy-in' to the TB programme, for example reimbursement of some costs associated with TB testing of infected deer herds and 'topping-up' compensation for dairy farmers when TB reactors from clear herds were found to be non-tuberculous.

- heavy reliance on evidence-based development of strategy and policy underpinned by commissioning of TB-focussed research and development such as:

- early demonstration and acceptance that possums were the main vector of TB for cattle and deer.

- development and adoption of the Residual Trap Catch Index (RTCI) (NPCA 2013, Warburton and Livingstone This issue) as a consistent and affordable standard method for estimating possum population abundance. This enabled informed decision-making as to the intensity of possum control required to best meet TB control goals, and provided a quantitative tool for measuring the effectiveness of control operations. This in turn provided the basis for a commercially contracted, performance-based possum control programme. major technical gains made in controlling possums through research and management improvements, including greater precision in aerial 1080 baiting operations supported by GPS technology and increasing knowledge of possum behaviour at low population densities

- elucidation of the epidemiology of TB in other wild animal species which has also identified roles as sentinel animals

- modelling that supported operational findings that TB could be eradicated from infected possum populations if they are held at low densities for a minimum of five years and there was no immigration of TB possums.

References

- Bovine TB control: what are other countries doing? Farmers Weekly Interactive. July 2011.

- New Zealand. www.bovinetb.info

- Why is New Zealand known as a world leader in the control and management of bovine TB? Interview with Paul Livingstone. www.tbfree.org.nz. Downloaded August 2013.

- Badger cull thoroughness. www.bovinetb.info